I recently finished putting the photos from a weekend down in south-west England up on my Flickr photostream. A moderately frenetic two days, that - we got as far as Cornwall, without Angela having to take any time off work - but fun.

I recently finished putting the photos from a weekend down in south-west England up on my Flickr photostream. A moderately frenetic two days, that - we got as far as Cornwall, without Angela having to take any time off work - but fun.To start with, it gave Angela an excuse to try a return visit to the Methuen Arms, in Corsham, which once upon a time was legendary among her colleagues as a place you booked to stay on business once, so you'd know not to go there again. Suffice to say that it's changed hands since then, and been changed completely, and now it's a very nice place to spend a Friday night, with a good restaurant and all. However, that was just a first-night stopping place, as the next day, the 24th of March, we were on the road again for a few hours.

The primary destination for the day was the Lost Gardens of Heligan, which we hadn't managed to fit into previous trips down west in recent seasons. For those who don't know of them, these are the gardens of a rather grand country house which fell into total decline and decay in the latter part of the 20th century, until they were rediscovered a few years ago by someone who has managed an extraordinary feat of horticultural resurrection.Nonetheless, and despite being quite rightly full of enthusiastic visitors, they still have a slightly wild feeling in places - one part is quite plausibly known as "The Jungle" - while having been restored to enclosed formality in other parts. A good place to see, even if you're not especially fascinated by gardens as such; there's a definite feeling of an old-time private estate, with everything from Italianate formality to woodland walks, poking through a thin layer of time. Plus some fairly weird sculptures.

The primary destination for the day was the Lost Gardens of Heligan, which we hadn't managed to fit into previous trips down west in recent seasons. For those who don't know of them, these are the gardens of a rather grand country house which fell into total decline and decay in the latter part of the 20th century, until they were rediscovered a few years ago by someone who has managed an extraordinary feat of horticultural resurrection.Nonetheless, and despite being quite rightly full of enthusiastic visitors, they still have a slightly wild feeling in places - one part is quite plausibly known as "The Jungle" - while having been restored to enclosed formality in other parts. A good place to see, even if you're not especially fascinated by gardens as such; there's a definite feeling of an old-time private estate, with everything from Italianate formality to woodland walks, poking through a thin layer of time. Plus some fairly weird sculptures. We'd hoped to follow this up with a quick visit to the nearby Eden Project - we still had tickets from our visit last year which are good for twelve months, darn it! - but unfortunately, that was still on its winter opening schedule, and was closed by the time that we got there. So we rolled on, diverting a short distance for a brief visit to the real Jamaica Inn (just looking round the outside, really), before driving on to spend the night in Okehampton.

We'd hoped to follow this up with a quick visit to the nearby Eden Project - we still had tickets from our visit last year which are good for twelve months, darn it! - but unfortunately, that was still on its winter opening schedule, and was closed by the time that we got there. So we rolled on, diverting a short distance for a brief visit to the real Jamaica Inn (just looking round the outside, really), before driving on to spend the night in Okehampton.

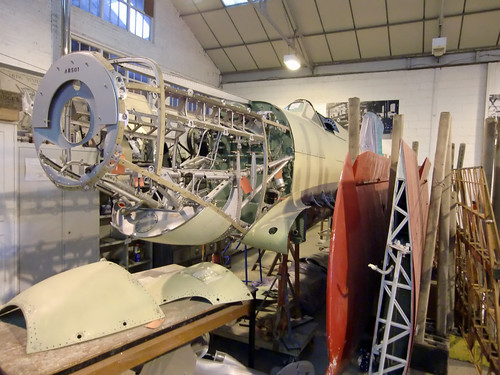

The next day (the 25th of March), we were heading back eastwards - but with a stop planned. We'd seen flyers for the Haynes International Motor Museum, and we thought it sounded interesting. We were right. I suspect that this is the biggest motor museum collection in the country, lurking in a giant shed or two in Somerset, and it probably deserves to be better known. It's currently undergoing a bit of refurbishment and expansion work, but even so, it combined aesthetically impressive experiences (some fabulous designs from multiple eras) with twinges of sometimes downright painful nostalgia (several iffy 1970s models that I thought were really cool in my early teens). Probably only a motor museum can do this quite so effectively.

The next day (the 25th of March), we were heading back eastwards - but with a stop planned. We'd seen flyers for the Haynes International Motor Museum, and we thought it sounded interesting. We were right. I suspect that this is the biggest motor museum collection in the country, lurking in a giant shed or two in Somerset, and it probably deserves to be better known. It's currently undergoing a bit of refurbishment and expansion work, but even so, it combined aesthetically impressive experiences (some fabulous designs from multiple eras) with twinges of sometimes downright painful nostalgia (several iffy 1970s models that I thought were really cool in my early teens). Probably only a motor museum can do this quite so effectively. (A note on the name and origins of this museum, mostly for the benefit of non-UK residents; the Haynes motor manuals are a very useful line of independently-published workshop manuals. The chap who founded the company was evidently a serious car enthusiast, and his collection formed the core of this collection.)

(A note on the name and origins of this museum, mostly for the benefit of non-UK residents; the Haynes motor manuals are a very useful line of independently-published workshop manuals. The chap who founded the company was evidently a serious car enthusiast, and his collection formed the core of this collection.)

Among the aesthetic positives, by the way, was a real, honest-to-God 1931 Duesenberg. We stumbled across this early in the tour, although I think it's meant to be a bit of a climax for a visit, because the current building work means that visitors end up going round the place in the reverse of the usual direction. This name may not mean very much to Europeans reading this; it wouldn't have meant very much to me before this trip. But let's just say that this thing is unique in Europe, one of eight of its kind in the world - and if you were drawing a comic strip set in the 1930s USA, and you wanted to show that some rich or powerful character had some degree of taste or style, this is the car which he'd arrive in. It's an authentic work of art.

Among the aesthetic positives, by the way, was a real, honest-to-God 1931 Duesenberg. We stumbled across this early in the tour, although I think it's meant to be a bit of a climax for a visit, because the current building work means that visitors end up going round the place in the reverse of the usual direction. This name may not mean very much to Europeans reading this; it wouldn't have meant very much to me before this trip. But let's just say that this thing is unique in Europe, one of eight of its kind in the world - and if you were drawing a comic strip set in the 1930s USA, and you wanted to show that some rich or powerful character had some degree of taste or style, this is the car which he'd arrive in. It's an authentic work of art. Anyway, having finished there, we were able to get home in reasonable time, even stopping briefly on the way to take a quick look at Stonehenge over the surrounding fence. So I ended up with a lot of photos.

Anyway, having finished there, we were able to get home in reasonable time, even stopping briefly on the way to take a quick look at Stonehenge over the surrounding fence. So I ended up with a lot of photos.