When we - the general public - go to museums, we tend to think of them in terms of the stuff that we see on display. Which is fair enough, but - to a degree doubtless varying with the museum - also wrong. There's a whole load of curating and preservation and additional material and scholarship going on behind the scenes, which we glimpse in dribs and drabs if we pay attention.

The Fitzwilliam's current big exhibition of Italian Drawings, which we went to see on Saturday, reminded me of this, with something of a kick. It draws largely from the museum's own back rooms - items which aren't normally on display. But one motive for going to see it is, frankly, something akin to name-dropping. It's not often that one gets a chance to see art by (among others) Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, Vasari, and Modigliani, all in the same room, within a dozen miles of one's front door, after all. Okay, so what one sees is actually a bunch of, well, drawings, ranging from quite stylish but dashed-off pen-and-ink pieces to tiny preparatory sketches and doodles. But the raw density of art history in that one room is quite impressive.

That's one fairly dimly-lit room, mind. One reason that some of these highly significant pieces can't regularly appear on display is clearly that, even more than a lot of art, they're fragile. I won't quite say that they're disintegrating before one's eyes, but some of them certainly look lucky to have lasted this long, and despite all the technical brilliance of modern museums, I'd guess that they have a finite lifespan, even if it can still be measured in centuries. There's a definite sense of the memento mori when one looks at a tiny, fading sketch that was in fact dashed off by Leonardo when he was thinking about how to depict horses and riders, five hundred years ago.

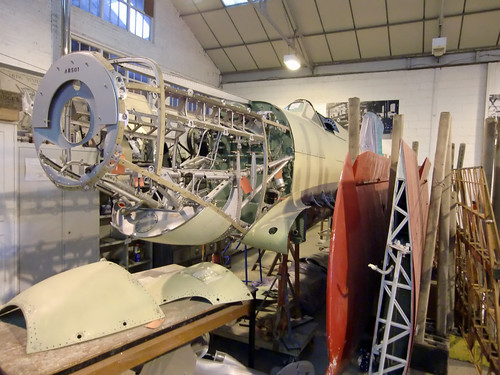

Then, on Monday, we went to a completely different museum which has an equally important backroom function - the Shuttleworth Collection in Old Warden. For those who don't know it - this is a fairly substantial aircraft collection, but most impressively, it's got some old aircraft. That is to say, they have a couple of planes, in actual flying condition, which are over a hundred years old. This puts them in the business of restoration and preservation as much as any museum, which is something they happily talk about; for example, they have a Spitfire (pretty much inevitably, I guess), and one can see it in one hangar - in bits. It needs sprucing up, it seems.

Mind you, aircraft restoration evidently involves a lot of refitting and replacement work. The displays talk about the art of fitting new fabric surfaces (so with some of these aircraft, most of what meets one's gaze is actually new) and the necessity of replacing, say, thousands of magnesium rivets with something newer and less lethally corrosive. But aircraft are machines, built to do something; a restoration process that kept more of the original but left it incapable of flight, would perhaps be too much like taxidermy.

(I grabbed a fair few pictures on Monday, incidentally, of aircraft and also of the adjacent Swiss Garden and Bird of Prey Centre. I'll try and get them up on my Flickr photostream reasonably soon.)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

The attempt to get everything they can into flying condition actually makes the Shuttleworth Collection quite unusual among aero museums; many of them go for historical interest and original-parts instead. (Most of them don't have runways, of course.) Then there are odd hybrids like the de Havilland museum near London Colney, where they're trying to get things into flyable state but have to haul them out by road if they want to fly them...

Post a Comment